Bikes and Parking Places

I’m a huge fan of saving years of seemingly useless data and then trying to make sense of it. If I see a (sort-of) publicly available datasource that I can scrape and save I jump on it. It started with bike and moped sharing and later continued with “smart parking”.

In this post I’m going to explain the process of finding, obtaining and archiving these datasets and will follow up with analysis later.

Bikes and parking places

It all started with Bubi, a public bike sharing network in Budapest. Then it continued with the moped sharing blinkee application and later with smart parking.

What these all have in common is that they have some app or website where you can check their current state (bike locations, free parking spots, etc.). If there’s an app, there’s a datasource behind it and it turns out these are sort-of publicly available.

Obtaining the data

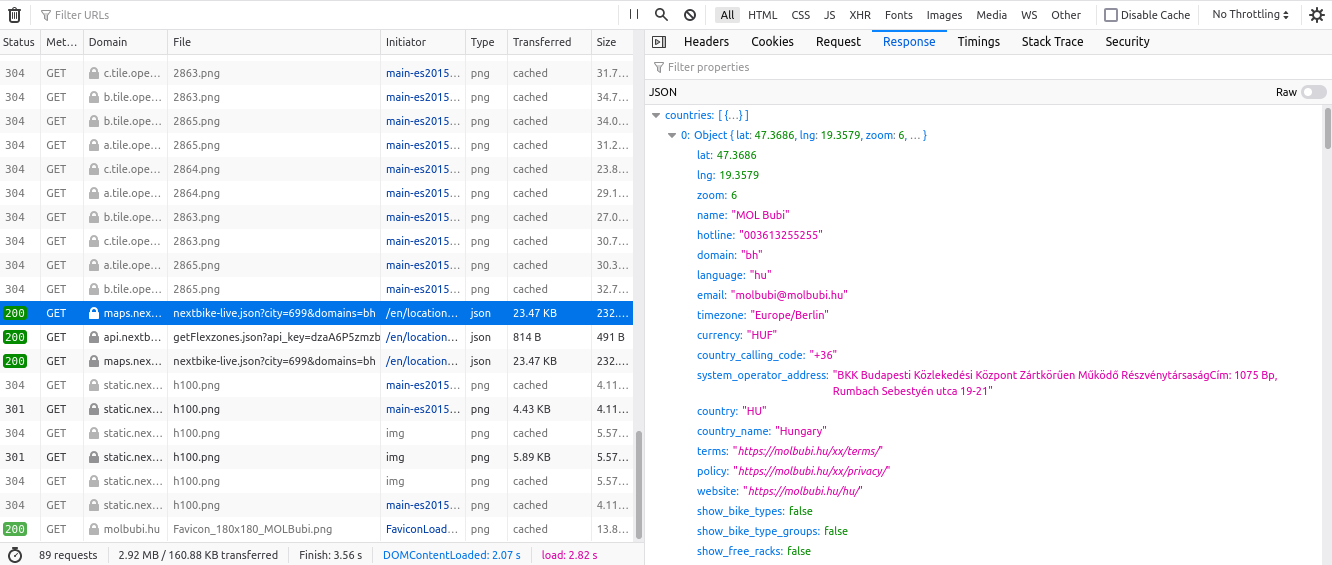

As far as I can tell none of these services publicly advertise their APIs. However they also don’t seem to be actively trying to block “outside” access to them. This means that getting the data boils down to finding the URL you need to download.

For some services this is as simple as opening their website in a browser and checking the outgoing requests:

For others, when there’s no web access – only a mobile app – you might have to set up a MITM proxy that routes all traffic through your computer where you’re able to sniff it. If they use HTTPS (which they should and usually do) then you need to jump some extra hoops to get your own certificate accepted by your phone.

Is this legal?

Short answer: I have no idea. However, I don’t think that this should be a real concern for any of the services. My rule of thumb was to keep the load I’m generating similar to a “legitimate” user’s. E.g. if the website only refreshes the data every minute, I’m also only getting it once a minute.

To indicate that I mean no harm and make their life easier if they ever decide to block my requests I’m also including the following constant HTTP header in all my requests (with a different value):

x-block-me-if-you-want: taimocbknbzxntsyklkobvcw

Also, my requests always come from the same IP address.

What to save

So I have an HTTP API endpoint that gives me an JSON/XML response with the whole state of the service every time I call it. What exactly should I save?

Dummy but safe

Trivial answer would be to save the whole response every time and this is what I started with.

I think this is generally a good approach. If you’re going to process your data later and don’t know exactly what you’re interested in at the time of saving, it can’t hurt to save everything (assuming that paying for storing tens of gigabytes of data doesn’t hurt).

Implementation

This approach is really this simple:

1DT=`TZ=Europe/Budapest date "+%F-%H-%M-%S"`

2

3y=`echo $DT | cut -b 1-4`

4m=`echo $DT | cut -b 6-7`

5d=`echo $DT | cut -b 9-10`

6dir="$y/$y-$m/$y-$m-$d"

7mkdir -p /path/to/save/data/$dir

8wget -qO- --header='x-block-me-if-you-want: ...' 'https://example.com/some-api' | gzip > /path/to/save/data/$dir/$DT.xml.gz

Making these year/month/day subdirectories not only helps organize your data but also to overcome filesystem (and blobstore) limitations around number of files in the same directory (or bucket). It also makes archiving easier. More on that a little later.

Incremental approach

The problem with saving everything is that you can end up with a lot of data quite quickly. A single response from the smart parking API is around 800kB. Save that every 5 seconds for a day and you will end up with:

800kB * (60 * 60 * 24 / 5) = 13.824gB

Gzipping would help but it’s still more than I’d like to store for such (seemingly) useless data.

If you scrape an API every five seconds, you’ll notice that not much changes in that time. The smart parking datasource shows 3-5 changes per 5 seconds in peak hours. It would be enough to only save the changed parts and the whole state could be recovered at any moment in the past. This is the idea behind incremental backups.

But what classifies as a “change” and what is a “changed part”?

Every datasource I’m crawling contains some kind of list. List of bike racks or list of parking places. Changed part means an item in this list, so a single bike rack or a parking place. Change means any kind of change to an existing item or the appearance of a new item (e.g. when a new parking place is installed).

For an average day, this results in storing around 70mB instead of 13gB which is a huge improvement. Gzip that and it’s only around 1mB per day.

Implementation

Obviously this approach requires understanding your data to some extent (where

is the list I’m interested in) and some logic that differentiates between states.

I’m running a little service written in Go that scrapes the APIs and does the

incremental backup in the same year/month/day directory structure as the

dummy approach.

Some details:

- Prepare for failure: If the application dies (e.g. if I were to forget handling network failures gracefully), a new instance should be able to pick up where the old left off. This would require reading all the previous increments to re-construct the current state. To avoid having to do this (would be very slow and I also don’t want to keep every previous increment in the local file sytem) I’ve ended up always saving the full current state into a “backup” file. This is also useful when upgrading the application to a newer version.

- Preprocessing: some metrics are easy to generate when detecting a change and it makes sense to store them with the data. E.g. storing the previous state and the time it has last changed.

- Live data: The application is also publishing events (changes) in real time on a WebSocket endpoint.

- Live analysis: I’ve ended up loading the data into Elasticsearch later on. Then I’ve extended the application with loading the events into Elastic in real time.

Archiving

Both approaches outlined above will leave me with data as files in the local file system in the following directory structure:

├── data

│ ├── 2021

│ | ├── 2021-08

│ | | ├── 2021-08-10

│ | | | ├── 2021-08-10-00-00-04-+02.json

│ | | | ├── 2021-08-10-00-00-09-+02.json

│ | | | ├── ...

│ | | ├── 2021-08-11

│ | | | ├── 2021-08-11-00-00-04-+02.json

│ | | | ├── 2021-08-11-00-00-09-+02.json

│ | | | ├── ...

│ | | └── ...

│ | ├── ...

Local store would fill up quickly if I kept adding files this way. So instead of keeping everything locally, I’m archiving data in daily chunks to Scaleway’s Object Storage (an S3-compatible blobstore) where storage capacity is (seemingly) infinite if you’re willing to pay the price. First 75gB is free though.

1#!/bin/bash

2#

3# This script aggregates yesterday's parker data and uploads that

4# to Object Storage. Invoked from cron every morning.

5

6cd /mnt/data

7TMPDIR=/tmp/parker-upload

8mkdir -p $TMPDIR

9

10# Get yesterday's directory

11DT=`TZ=Europe/Budapest date --date=yesterday "+%F"`

12y=`echo $DT | cut -b 1-4`

13m=`echo $DT | cut -b 6-7`

14d=`echo $DT | cut -b 9-10`

15dir="parker/data/$y/$y-$m/$y-$m-$d"

16

17# Compress into a tar.gz

18DAILY_NAME=$TMPDIR/$DT.tar.gz

19tar -czf $DAILY_NAME $dir

20

21# Upload to Object Storage

22UPLOAD_PATH=$dir.tar.gz

23aws s3 cp $DAILY_NAME s3://$UPLOAD_PATH

24

25# Remove from local FS

26rm $DAILY_NAME

27rm -r $dir

Conclusion

This has covered how I’ve ended up with gigabytes of seemingly useless data. In the next post I’ll describe the datasets in a little more detail and will try to find interesting patterns in there.